A Call to Return to Consciousness Raising

Winnie Lark explores how blending radical traditions with modern digital tools can empower women to connect, organize, and take action.

By Winnie Lark

After Trump was elected a second time, I was shocked to see women in America speaking online about the 4B movement. 4B, a radical feminist initiative that originated online in South Korea, derived its name from four tenets that all begin with "bi," a Korean term roughly translating to "no." The four “nos” of 4B are as follows: no sex with men, no giving birth, no dating men, and no marriage with men. Following an election where the majority of American men voted against women’s interests, American women were desperately searching for something to do in response. Considering that their reproductive rights were on the line, 4B started to make sense for some.

The principles of 4B sounded shocking to the average American, and men and women alike began to lash out at the fact that these ideas were even being discussed. On Twitter and TikTok, the masses argued over whether or not 4B was anti-feminist, transphobic, or just plain useless. TikToks featuring women announcing their intention to follow 4B gained hundreds of thousands of views. As I scrolled through these videos, I stumbled upon related TikTok Lives. Unlike traditional Lives, where creators spoke directly to the camera, these featured a graphic in the background posing a question such as, "What do you think about 4B?" Along the side, you could see the small circles of the profile pictures of up to 9 other TikTokers who were given permission to speak. People clamored for the opportunity to respond to the question, and there were thousands of people watching the debates. Liberal feminists, conservative Christian women, alt-right men and more were voicing their opinions, and the chat rallied in support of or against the speakers.

What I saw was fascinating. A radical feminist movement was being discussed widely on TikTok, of all places. These TikTok Lives lasted for hours and would often shift from debating 4B to sharing personal experiences with misogyny.

One night, I watched a Live that had shifted topics to how feminists in America should be actively reaching out to other women. One woman shared, “my aunt still doesn’t understand that her husband should be doing the dishes.” The women in the Live joined in with their own anecdotes about how shocked women in their personal lives were when they told them that their husbands should be doing chores around the house. I thought about how, maybe, there were women watching this TikTok Live that had for the first time had their feelings validated. Maybe this was the first time that anyone had told them that their husbands should be doing the dishes. Now, on this app, they had a little seed planted in their consciousness—things weren’t as they should be. I realized that these conversations were small moments of feminist consciousness raising. It was made clear that women were desperately feeling the need to speak out and speak to each other.

After the discussions I witnessed between women online and in person, I believe that now is the perfect time to return to the radical feminist tradition of consciousness raising. In “Consciousness-Raising: A Radical Weapon,” originally written in 1973 and published in Redstockings’ Feminist Revolution (p. 144), Kathie Sarachild outlined what feminist consciousness raising is and how it worked. It began as a practice when the women’s liberator group New York Radical Women realized that “in order to have a radical approach, to get to the root, it seemed logical that we had to study the situation of women, not just take random action.” At a meeting, one member of the group, Ann Forer, mused out loud about how she had only recently begun thinking about women as an oppressed group. She stated, “I think we have a lot more to do just in the area of raising our consciousness.” This struck a chord with the other members of the group, and in their next meeting, they debated how best to go about consciousness raising.

What arose from that meeting was a program for consciousness raising (CR) that would be utilized at all future meetings. The women decided they should study women’s lives. They read theory on their own and brought what they learned back to the group. However, in a world dominated by ideas about women mostly created by men, they wanted to see if their actual experiences aligned with the theories they had studied. In “About My Consciousness Raising”, Barbara Susan says:

“[c]onsciousness raising is a way of forming a political analysis on information we can trust is true. That information is our experience. It is difficult to understand how our oppression is political unless we first remove it from the area of personal problems. Unless we talk to each other about our so-called personal problems and see how many of our problems are shared by other people, we won’t be able to see how these problems are rooted in politics” (“Redstockings First Literature List And A Sampling of Its Materials,” 1969, p. 44).

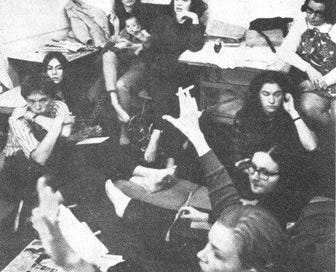

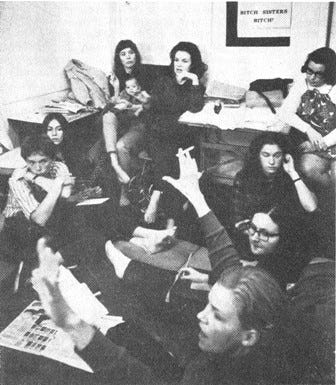

At CR meetings, women would go around the room, one person at a time, and answer a question that was posed to them, such as, “Who and what has an interest in maintaining the oppression in our lives?” As each woman answered, the others would listen, learn, and sometimes go off on tangents when they came to important realizations. After these digressions, the group always returned to the central goal: understanding shared oppression and identifying actions to create change. As Sarachild explained, “The idea is to study the situation to determine what kinds of actions, individual and political, are necessary” (Consciousness-Raising: A Radical Weapon, p. 149). New York Radical Women made their first public action after consciousness raising at the 1968 Miss America contest, where they protested beauty pageants by throwing girdles, high heels, razors, and “other objects of female torture” into a “Freedom Trash Can.” This action gained widespread attention from horrified anti-feminists and spurred the enduring myth that feminists in the 60s burned their bras.

In 1969, Judith Brown’s handbook published by Redstockings called “How to Start a Group” provided practical advice for other women that wanted to start their own CR groups. Things were different in 1969—women didn’t have the option to connect over Twitter or TikTok. For finding other women to start groups with, she recommended “getting your friends together, calling a caucus in a male–female group you belong to, getting a women’s group you belong to to deal with women’s liberation, placing ads in newspapers,” and most importantly, “distributing literature” (p. 1–3). In many of these suggestions, she adds anecdotes of women who had been inspired by feminist literature that had been given to them. For example, she recounts about one woman in a southern town:

“This woman had also read a pamphlet about the oppression of women. She got up in the faculty wives club and told about the pamphlet. She complained that women hardly ever talk to each other, and when they do, they often avoid certain topics. She gave examples of some of the unmentionable topics, several of which are listed as (CR) questions in the Appendix. Some of the women there agreed with her, and they decided to attend a meeting at her home about these questions” (p. 3).

When scouting out women for a CR group, Brown recommended speaking to women individually, and never in the presence of a man or her supervisors so as not to put her on the spot. Next, she recommended handing out literature, or even suggesting “movies or television programs which show clearly how women are oppressed by men.” “It is never absolutely necessary to hand out literature in advance, however,” she stated. “You may know that none of it is right for the woman you know. In that case one of the things your group will want to do is write something that appeals to other women like themselves.” She especially recommended giving her handbook to others in advance of their first CR meeting. “We think that because all women are experts on women, that we can all evaluate literature like this Handbook and then be responsible for helping in the group to carry out our goals. …Sometimes we call ourselves the “conveners” of meetings since we don’t try to run them, and can’t anyway” (p. 4–5).

So how should one expect a consciousness raising meeting to go? In 1998, Gainesville Women’s Liberation created a consciousness-raising organizing packet featuring Kristy Royall’s essay “What is Consciousness-Raising?” which contained a great general outline for feminists to follow. “Start out with a set of questions that each person in the group answers as honestly and completely as possible. Make sure that participants answer from their personal experience, not what they read in a book or what they think are problems in general.” She warned against letting CR meetings devolve into “group therapy.” This was avoided by setting time limits on each person giving their testimony, alerting participants when they began speaking generally as opposed to personally, as well as leaving ample time at the end for coming to conclusions (p. 19).

This is where the Tiktok Lives that I enjoyed watching fell short. While it was great to see those conversations getting started, since they were conducted without a structure and purpose in mind, they ultimately served only as disjointed venting sessions. As Royall stated, “Without at least trying to draw conclusions, CR becomes merely a rap group, a place to meet other people and get things off your chest. The data is full of potential, but without conclusions its power cannot be unleashed. Conclusions is the part of CR where individuals’ experiences are transformed into general theories that we can actually use to make decisions about our organizations and about our movement” (p. 20).

Royall suggested a few beginner questions: “When has a man expected something of you that you didn’t want to do? Did you go along with it? Why or why not? What did he stand to gain if you went along with it? What did he stand to lose if you didn’t?” “When have you used the way you look to get something? Why? What happened?” “Have you ever lived with a man? What did you like about it? What did you not like?” (p. 19). While members answered in their allotted time, there would be a designated note-taker recording testimonies. All names and details which could reveal a person’s identity were removed. She stressed that testimonies and conclusions from CR must be shared so that other women had the chance to learn from the group’s observations. After all the data had been gathered, members worked together to pool and compare the experiences they heard about, paying special attention to contradictions between peoples testimonies, as often there was a common root problem. Royall advised that “Sometimes these contradictions can show us that there is not an individual solution, because we hear testimony from women who have tried different strategies. For this reason it is important to hear testimony from people with a variety of backgrounds (racial, cultural, and economic) or living conditions (married, single, divorced, with children, without children, older, younger, etc)” (p. 20).

I believe there is no better time than now to begin a consciousness raising revival. Women across the world are acknowledging their feelings that something isn’t right and beginning to voice their dissatisfaction. We have a responsibility to seize this moment and amplify it. Radical feminists in the late 60s were opening their homes to each other to make spaces away from men and speak about their oppression. This led to brave actions being taken and great changes being made. We are now in a digital age where we have the opportunity to connect with women across the world, as well as easily accessing resources provided by the feminists who came before us. While I firmly believe in the value of in-person consciousness raising meetings to foster local feminist communities, I think we seriously need to consider what we’re capable of doing online. By blending traditional CR practices with modern technology, we can create a powerful movement for collective liberation. I encourage all radical feminists to begin a consciousness raising group, be it in your local communities or online.