An Argument Against the Female Nude: Abridged

"We, as feminists, must be able to recognize the misogyny encoded in visual depictions of women especially when considering the ubiquity of images in our culture."

By @FemFederation

This is an excerpt from a longer essay that will be featured on my Substack. This section discusses Venus/Aphrodite as the prototypical origin of the conventionalized female nude in Western Art. Artistic nudity is often positioned in opposition to pornography to determine what type of nudity is culturally appropriate—especially Classical nude sculpture. I argue that from its inception, however, artistic female nudity has been a product of patriarchal society and has historically functioned as erotica for an elite male ruling class. I encourage using the methodology I have employed in this essay (visual analysis, historical context, and feminist theory) to assess works of art and images of women in your own life.

When walking into any art museum in the Western world, there is a not insignificant chance for one to encounter artistic depictions of nudity. There is an even higher chance that the majority of these depictions are of nude female bodies, specifically.

Aphrodite, better known as Venus, is the prototype that underscores not only the artistic tradition of the nude, but representations of women in Western visual culture as a whole. Venus imagery is present in everything from adverts to television to pornography, and even informs the contrapposto position (one leg bent, knees together, and hips cocked) that so many women assume when in front of a camera. (I am here referencing John Berger’s Ways of Seeing: watch Ep. 2 on YouTube; or read it online.)

Venus appears again and again in Western Art: she stars in Botticelli's Birth of Venus; she is turned on her side and made reclining by Titian in Venus of Urbino; & Picasso’s Demoiselles D’Avignon borrows from Classical depictions of Venus washing her hair; and she appears repeatedly in Zoffany’s The Tribuna of the Uffizi (c. 1772–1778), pictured above. Venus is the mother of all female nudity in Western Art: to understand her is to understand the nude tradition一and because the female nude is not merely a recurring subject, but the fundamental subject (Berger), to understand Western Art itself.

The first work of Western Art to depict a fully nude female was Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos (c. 360–330 BCE). It was widely lauded as one of the sculptural masterpieces of the classical world and spawned numerous extant copies, made in both the Classical era and the later Renaissance. It is the nude from which all nudes are descended.

The Knidian Aphrodite was also one of the first and most significant examples of erotic art in the ancient world, becoming an erotic tourist attraction in antiquity. Pliny the Elder described the statue as “not only the finest work by Praxiteles but in the whole world,” and wrote that many visitors were so overwhelmed by the statue’s eroticism that they had to be stopped from masturbating in its presence (Bellis). This tourism is further recounted by feminist art historian Catharine McCormack in her book Women in the Picture (p. 35):

“Once they were alone in the sanctuary with the marble figure, one friend tried to kiss it on the lips, while the other, who was homosexual, went for her buttocks, claiming that they were as arousing as those of any young boy. The friends also noticed a stain on the statue’s thigh… [of which the priestess custodian explained] that a sailor had ejaculated on the statue when trying to have sex with it.”

If you find this surprising, you’re not alone. Many art institutions, especially in the US, have discouraged (or outright denied) erotic readings of nude art: firstly via the doctrine that female nudity in art is an ‘appreciation of the female form;’ and secondly, in an attempt to assuage anxieties about the nature of this ‘appreciation,’ via the commonly repeated adage: it’s not sexual, it’s art.

This dichotomy suggests that for something to be a ‘great work of art’ it cannot be sexual in nature, and that sexualized depictions of nudity are not and cannot be ‘great works of art.’ Moreover, fine art is often positioned in opposition to pornography to exemplify what sort of nudity is culturally appropriate. However, as the above passage shows, female nudity in art has been sexualized since its inception. It is crucial for us as feminists to reject this dichotomy and recognize the eroticized misogyny embedded in artistic depictions of women in Western Art.

This essay intends to expose the very important truth that the Knidian Aphrodite and its many descendants are both sexual and art. To understand what the Knidian Aphrodite meant to contemporary Classical audiences and what makes her so erotic, we must look to the origin of both male and female nudity in Western Art: Classical Greece (the 5th and 4th centuries BCE).

Ancient Greece had a thriving artistic tradition of “heroic male nudity,” referring to the armor-like physiques bestowed upon representations of Classical heroes (Herring). The musculature of male nudes artistically represents the heroic virtue, or kalokagathia, meaning “beauty and goodness, conceived of as an inseparable pair” (Kousser p. 149), of the subject.

The Discobolus, sculpted by Myron of Eleutherae in the fifth century BCE, is regarded as one of the most influential pieces of Classical art ever made and is particularly lauded as a visual representation of kalokagathia. Interestingly, the Discobolus’ abdominal musculature is anatomically incorrect (Beard, Shock of the Nude, 25:35). Despite the perceived accuracy of Classical sculpture, artists sculpted the body to display the subject’s character, not their appearance.

Female nudity first appeared in Classical art as sexualized depictions of courtesans (hetaira) or prostitutes (porne) painted on pottery (Beck p. 1847; Women in Antiquity p. 42). Ancient Athens had a thriving yet ambivalent culture of prostitution: brothels were state sponsored but prostitutes of all ranks were “not considered morally or lawfully worthy of sacred Athenian citizenship, marriage, or public ceremony” (Beck p. 1847). Having sex with prostitutes allowed for Greek males to exercise their sexual superiority as virtuous democratic citizens and express their authority via penetration without impinging on the virtuosity of Athenian women (Beck p. 1848). Artistically, prostitutes were depicted in unflattering ways that, by inverting kalokagathia, visually represented their poor moral character.

In Ancient Greece, virtuous females were always depicted fully clothed, as chastity was the most important virtue for Athenian women (BBC). Respectable women were expected to wear a veil on the rare occasion they left their house at all (Beard “Women in Power” 18:45). The Grecian understanding of artistic male nudity as heroic & virtuous and of female nudity as immoral and erotic served to sexualize and degrade the female body & sex-class whilst venerating the male body & sex-class.

However, the first significant fully nude female sculpture was not of a prostitute—but of a goddess.

Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos is fully nude and sculpted in contrapposto position. Her genitals are modestly covered by her hand and the line of her bent arm leads the eye up to her abdomen and breasts. Her other hand clutches drapery that leads down to a bathing urn, both supporting the otherwise free-standing sculpture and telling the viewer that the goddess was undressing for a bath.

The inclusion of both a bathing urn and drapery is significant for multiple reasons: firstly, it humanizes Aphrodite by showing her engaged in a mundane activity. Secondly, it connects Aphrodite to her mythological origin of sea-birth—on the island of Knidos, Aphrodite was particularly invoked as a water goddess and given the epithet Euploia (fair sailing) (Kousser p. 150). Thirdly, it provided a moral context for the goddess’ nudity. As nudity typically denoted prostitutes, the bath setting made the goddess’ nudity socially acceptable.

However, by humanizing the goddess, Praxiteles allows societal views about nudity, patriarchy, and sexuality to color the interpretations of his sculpture. The inclusion of a bathing urn here becomes important for a fourth reason: Aphrodite clutching her robes transforms the nudity of this work from allegorical to literal: this formal component suggests that she has just disrobed. In other words, it suggests movement. It makes it real.

Unlike Classical examples of other goddesses, Aphrodite is looking to the side. She is unable to meet the viewer’s gaze and assert herself as an equal. Interestingly, this reminds me of a formal convention deployed in paintings of prostitutes in which the male’s head and eyeline are higher than that of the females’ as a visual representation of female inferiority (Beck 1848). Some scholars believe that Praxiteles modeled the Knidian Aphrodite after a courtesan he patronized, named Phryne (Louvre). If this was the case, Aphrodite’s averted gaze and full nudity may be references to the artistic conventions typically used to denote a prostitute. This contradicts the interpretation of her nudity, pose, and bathing as mythological aspects.

The Knidian Aphrodite is a chimera of elements which contextualize her nudity as virtuous and contain cult value, but also align her with the erotic conventions typically present in artistic female nudity. She is both ashamed of and calls attention to her nudity with the placement of her hand over her sex, adding mythological context (as Aphrodite was the goddess of sexual love and fertility) and an undeniable erotic charge. The bath setting provides just enough contextualization to preserve her virtue while also depicting a nude female body for the erotic pleasure of the male viewer. Her mythological elements provide a moral pretense not for her to be nude, but for male citizens to look.

The female nude is a reflection of male sexual superiority—that is its eroticism. It reinforces the ability of the male viewer to violate and sexualize female bodies by just looking at them.

While the original Knidian Aphrodite was lost to time, it spawned numerous copies in antiquity, including the Roman Medici Venus. This Venus deviates from the Knidian original by adapting the grasping of robes into a covering of the breasts: the iconic venus pudica pose. In this composition, the shameful modesty of the female subject trying to cover herself is contrasted with the voyeuristic gaze of the artist, patron, and viewer. This shame is never placed upon the male voyeur; female nudity is freely presented to be ravenously dissected by his gaze. After all, pudica comes from the Latin term pudendus, meaning both shame and vulva.

Similar to the Knidian original, the Medici Venus was famous for its eroticism. It was a popular stop on the Grand Tour, a pilgrimage to Paris, Venice, Florence, and Rome by upper-class European young men in the 17th to 19th centuries (Sorabella). This voyage served as the ultimate refinement of taste through the appreciation of art and culture—however, pilgrimages to see the Medici Venus and other ‘great works of art’ in the "Tribuna of the Uffizi “were as much about admiring Italian masterpieces as they were an exercise in culturally sanctioned leering over images of the female nude body” (McCormack p. 36). (This is rather neatly satirized in the Zoffany painting that began this essay.)

The mythological basis of nude art provided a moral context for men to voyeuristically enjoy female nudity whilst also reaffirming their social superiority: firstly over females as a sex-class, reinforcing their role as passive sexual objects; and secondly over lower-class men via familiarity with the mythological iconography used as moral context.

As the artistic subject, the nude is inseparable from the creation of great works of art and the canonization of the ‘genius’ male artists who created them. Nude compositions allow for artists to demonstrate their artistic & anatomical mastery and their familiarity with mythological iconography, compositions, & techniques used in famous nude precedents. In “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (1971) feminist art historian Linda Nochlin explains how mastery over anatomy, gained through life drawing, is one of the markers of a ‘great artist.’ Until the 20th century, however, female artists were barred from entering life drawing classes, creating an institutional barrier to their mastering of anatomy and the creation of ‘great works of art.’

The ubiquitous subject in Western art has therefore been almost entirely conventionalized, commissioned, and created by male artists and patrons. Nude art therefore contains a layered ‘male gaze’ (Mulvey): the female model is posed and directed by the male artist; represented via the art object in ways that will best please the male patron; who can then use the object for his own, usually erotic, means.

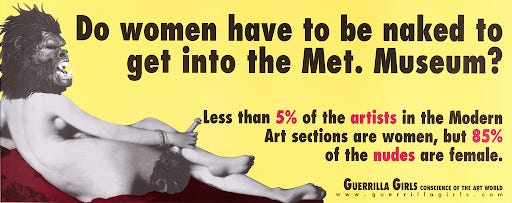

This inequality was famously highlighted by the Guerrilla Girls, first in 1989 (pictured below), then again in 2005 and 2012. The 2012 reissue has updated the number of women artists to be less than 4% and female nudes as 76% (Met Museum).

Interestingly, this implies that the museum did not acquire more work by female artists, but instead acquired more male nudes. As previously demonstrated, however, male nudes have historically functioned as a heroic power fantasy (or in the modern era, as gay erotica), whereas female nudes have functioned as sexual objects that encode misogynistic views of women.

This is present in the very origin of Venus, the nude’s prototype. In Classical mythology, Aphrodite/Venus functioned as a male-created representation of ideal sexuality. She was born not from a womb, but from the severed genitals of Uranus that were thrown into the ocean:

“where they frothed and transformed into a beautiful woman who was a goddess of love, beauty, and fertility…. The enduring Western symbol of feminine beauty and sexuality [came from] the sex organ of a man. Venus [Aphrodite] is the butchered testicle of her father’s body” (McCormack p 42–43).

Female nudity in Western art must be fundamentally understood not as an accurate representation of female nakedness and an appreciation of female sexuality, but as a culturally constructed artistic tradition that depicts women as erotic objects. Male artistic creation is a part of the economic and legal system of patriarchy, a system of sex-based oppression that is upheld with cultural beliefs, moral values, and artistic expression. The reality represented in painted, drawn, and sculpted images is just that—a fabricated reality formed from the vantage point, either conscious or subconscious, of its creator.

Rejecting the pornography-art binary exposes the historical weight of patriarchy and the active efforts of institutions to obfuscate the misogyny embedded in ‘great works of art.’ We, as feminists, must be able to recognize the misogyny encoded in visual depictions of women especially when considering the ubiquity of images in our culture.