Crimson Threads

Saaleha's poignant short story features a canvas with threads that come alive, allowing two Pakistani girls from different time periods to converse about turning quiet resistance into bold action.

By Saaleha

The world will not treat a quiet woman kinder than an insistent one. Amina knows this already. She quietly waits for the archivist to return with the diary she put on hold to use for her ethics paper. She is more of a vagabond than she cares to dwell on, fickle not in her convictions but in how she presents them. She holds her tongue more than she ought to and is an oafish fool who bites off more than she can chew. She had brought a bag of empty Red Bull cans to take to the recycling centre, but it would surely be closed when Carlos returned with her diary.

Carlos, the archivist, returns from behind the shelves and hands Amina the diary encased in protective film. ‘Due date’s on the back, my dear. I extended it for you.’

Carlos is the kindest man she knows. When university feels like a Frankenstein creation—a mesh of ivory-tower pupils who don’t care to know the world and an institution that beds great genocidaires—Carlos offers silent support to students in the opposite encampment. He does not even question the bag of cans over her shoulder.

Amina shoves the diary in her bag, bids him farewell, and walks briskly to the recycling centre some blocks away. The gate is shut with a rusted chain. Closed. Amina sighs. No point in dwelling on what is bound to happen. A streetcar takes her to her apartment complex. Passengers eye her as she sits before returning to their phones and books; downtown Toronto stuns Amina with how reclusive yet intrusive its denizens are. She figures the bag of clattering empty Red Bull cans at her feet doesn’t help the stares. A boy from her fluid mechanics class happens to sit across from her. He looks at the bruised spot where she had slammed a door into her face that morning, her worn fleece sweater, and then down at the bag. He offers her a tight smile and Amina looks away.

She thinks about the diary in her bag, the mystery in its pages. The library website indicated that it belonged to a 19-year-old Pakistani girl named Safiyyah, who was involved in ‘mutinous’ activities in 1971 to aid Bengalis against Pakistan’s brutality. It is weathered from the decades, which entices Amina.

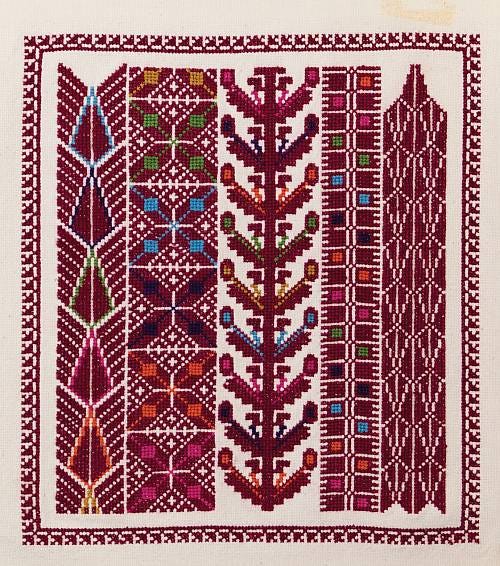

A parcel sits in front of her apartment unit, which Amina didn’t expect. She drops the bag of empty Red Bulls in the cabinet under her kitchen sink—a problem for another day. The kitchen knife glides against the cardboard and what is inside fills Amina with warmth. It’s a large, embroidered canvas. Intricate paisleys, flowers and geometric patterns decorate the canvas in reds, greens, yellows, and more against a white backdrop. A note is folded neatly atop the art. Miss Amina, perhaps you don’t remember me, it starts as Amina reads through it, but I am Lubna. Of course, she remembers her. Amina fulfilled a pillar of her faith in this act of charity and love by organising to evacuate this young Gazan mother to her family in Ottawa. I wanted to thank you, my sister. I made this for you. My daughter has joined a playgroup and I eat fresh fruit here. May God bless you. May you smell the fragrance of the highest heaven. Amina cannot help the way her throat constricts. Mothers should have sweet fruits and laughing children. And it is Amina’s university that labours to ensure Palestinian mothers have no such things.

Amina sets the canvas on her desk for now and absentmindedly tosses the diary on top of it to read and make notes later. She freezes when she hears a sharp ripping sound like cloth torn and thread ripped from fabric. She turns to look at the baffling noise and finds that the canvas seems to be undergoing some mutilation. The colourful thread moves on its own like a possessed viper travelling and convulsing across the canvas. Amina shrieks and trips over her feet, hitting the desk and knocking the canvas to the floor. The threads continue unfurling from the beautiful work Lubna created to become something not bound by earthly laws. Surely she is seeing things. Surely this is the result of slamming a door on her head earlier. She reaches a trembling hand over to touch one of the moving threads and it stings her before embedding itself back into the canvas. Amina cradles her hand and leans against the wall, watching the beauty become hellish. The threads eventually settle and spell something out. Amina, despite her fright, looks over to the bastardised canvas and finds the thread to spell, I cannot find my diary!

‘Whose diary?’ Amina whispers to the canvas. The words are pathetic to her ears. The thread remains still. She crawls to where the diary fell and stares at the pages that somehow are now empty. Some force, perhaps the same that made the thread sentient, makes Amina begin writing. She doesn’t care for whatever fine she’ll pay the library for damage.

‘Safiyyah?’ writes Amina with a trembling hand. The threads come alive again, violently ripping and embroidering themselves on the hemp and cotton to spell out a reply. Yes! I’ve done something not human.

Amina laughs madly. Not human, no, but it makes sense somehow. The fantastical element of reaching for some semblance of familiarity from the past, a plea to be understood by a stranger before you has become real in her hands. She writes back. ‘I’m Amina. I’m also 19 and Pakistani. I’m from 2024.’

The canvas dances with unearthly power as the threads rearrange themselves in reply. Hm. You have my diary, though. If Safiyyah is nonplussed at the absurdity of this act, her words don’t reflect it.

‘Yes. I’m using it as a source in my ethics paper.’

How odd. I lost it, now I use embroidery to hide codes for comrades.

‘Brilliant.’

The absurd exchange continues until Amina hears the dawn call to prayer from her phone. She had been writing to an enchanted canvas for hours with an equally enchanted diary. Safiyyah left to reconvene with her comrades as a communist protesting against her West Pakistani state for their actions against Bengalis. The canvas looks like a butchered animal. Some force had ripped the threads like someone ripping ribbons of camera film from a cassette to erase memories committed to celluloid. Amina lies down on her prayer mat and begs God to guide her in making sense of this. Her clasped hands reach not the grand, dusky sky, but her sorry popcorn ceiling. Does God care to hear the plea of a poor madwoman? Does He hear it from the wretched in Bangladesh? Gaza?

The threads that stitched Safiyyah’s words expressed that Amina shouldn't concern herself with who God hears when she has the means to do something about the world’s wretchedness and her own. It is Amina’s resignation to a bitten tongue and an open heart that keeps her so miserable.

Do you aid evacuating ladies of war? Safiyyah asks incredulously.

‘I do,’ Amina writes in the diary, ‘but behind a screen and with great effort.’

And you are a student of mechanics?

‘Yes.’

Then why haven’t you decimated those Israeli supply clippers you spoke of?

Good God! Amina almost tears the old page! That’s insanity. Whatever mechanical work Amina will produce will be to build, not destroy. The Zionist juggernaut does enough destruction. She has seen Palestinian mothers scream and tear at their clothes over the corpses of their children. She will not do the same to some quayside workers.

Amina completes her ethics paper in a month and receives a B. She forgot all about the infernal paper since her days and nights were occupied with feverishly writing in an old diary that belongs to a girl who speaks through spools of thread.

Things have gotten worse. Safiyyah says through the embroidered patterns. My dear comrade is in a coma. A brick to her head from a nationalist.

‘I’m sorry.’

No need. You have the means to do more than I do.

Amina knows she disappoints Safiyyah with her cowardice. She imagines Safiyyah. This confident woman would stare at men if they ogled her. A witty woman who wears her dupatta tied across her torso, not draped over her chest demurely. A wilful academic who gains her knowledge from the fields as much as she does from books. A brilliant revolutionary on the precipice of a great act. The five decades separating them were suddenly not the greatest distinction between them to Amina, it was rather Amina's knowledge of her own cowardice and eternal hesitance. The two women stood on opposite sides of a ravine, and where Safiyyah would jump, Amina would stand, willing herself to muster up the same bravery to no avail.

It is August of 2024 and Amina is kicking empty Red Bulls away from the walkway of her apartment. She hasn’t visited the recycling centre in a while. She hasn’t eaten well either, not with the finals of her summer physics courses. Nor has Safiyyah.

I heard of a bayoneted woman— a Hindu Bengali. Killed after birthing her child. The thread spells out the words unsettlingly slowly. A rape child. One Pakistani to rape her, another to kill her.

Amina closes her eyes. She’s read of the atrocities, but Safiyyah is there while it happens.

‘I can’t imagine.’

Sure you can. It’s happening there too, no?

Amina thinks of the Gazan women. Yes, it’s happening. The air is hot and stale here in her downtown apartment, she can’t think of the women having to give birth in humid tents only to be murdered by fire and drones and hunger. Intelligentsia from her academic institution fueling a genocidal one.

God forgive you for not heeding me, girl. I adore you. I’d adore your indignation also.

Amina stares at the thread. Safiyyah has been coaxing her to use her engineering knowledge for something militant. Amina now wishes she could.

‘I worry for you, Safiyyah.’ Amina writes in the diary. ‘You want gunpowder from my indignation, but I think yours will harm you, my love.’

As it happened, God would have to forgive Safiyyah for not heeding Amina. The last time the threads moved in their serpent-like way, they said, Militia forces crackdown in hostels. Us girls aren’t spared.

Amina frantically flips through the diary. Her writings to Safiyyah in the last months are gone like they were never there. Only the faded ink of the original diary, when she had first gotten it from the library, remains.

In the hours that follow, Amina spends hours on internet archives. Safiyyah Hayat. If she died in the summer of 1971, her name should be somewhere, for God's sake. She was the daughter of a Soviet-allied Pakistani literary giant. Dawn turns to dusk and Amina finds the name of the girl she had become besotted with. Death by firing squad ordered by the henchmen under the Butcher of Bengal with charges of mutiny and terrorism.

Amina leans back in the creaky leather chair. The stench of stale energy drinks and the sting of her bloodshot eyes are her only company as she thinks of what to do with her sweet friend’s death.

Amina has been waiting in a cafe at the Port of Saint John. Her hands are rough and burnt—all that work from welding the aluminium of empty Red Bulls and stolen motors from her university labs hurt. The clipper on the quay, carrying machines of death, is already unsteady, and soon, her makeshift Red Bull explosive would see to it that the ocean swallows it before it reaches people like Lubna and her children. Safiyyah had challenged Amina on what she already knew. Despite any comfort, a woman’s obeisance will not spare her from cruelty. Amina decides that if she remains in her comfortable silence, she must at least allow her machines to speak.