Resilience and Resistance through the Sahrawi Woman: The Struggle of Women from Western Sahara

Through the lens of postcolonial feminism, Salwa explores the layers of oppression Sahrawi women face and their pivotal role in the struggle for liberation.

By Salwa

Women are fundamentally perceived as a vulnerable group in situations of conflict. Having endured decades of conflict, Sahrawi women (indigenous to Western Sahara), are no exception. As this is a conflict with little to no media coverage, especially when it comes to sex and gender perspectives, it is interesting to analyze more about the effects of the war and the occupation on Sahrawi women and their roles in their society. This topic is also relevant as it pertains to an unresolved and ongoing struggle against colonialism and imperialism.

The focus of this essay will be on the oppression experienced by Sahrawi women due to war, occupation and the patriarchy of their own society. To align itself as closely as possible with the reality of the Sahrawi woman, the concept of “double colonization”, derived from postcolonial feminism, will be applied and elaborated further into this paper.

Postcolonial feminism is a response to Western feminism aimed at transforming the configuration of feminist and postcolonial studies by exploring the intersections of colonialism and neocolonialism with gender, nation, class, race, and sexuality in various contexts concerning women's rights and lives (Schwarz & Ray, 2000, p. 53). Postcolonial feminism opposes the widespread notion of the “universal woman” and the monolithic concept of the “Third World woman.” It demands recognition of the differences and cultural-historical complexities of women in different spaces and times, rejecting ethnocentric perspectives, the reproduction of orientalist thought, and acknowledging the global cultural-hegemonic power relations (Schwarz & Ray, 2000, p. 54).

Regarding the sources, a primary source I will be using is an interview I conducted in 2022 with Suelma Beiruk, the Minister of Social Affairs and Promotion of Women in the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) and former Vice-President of the Pan-African Parliament.

Historical Context

Western Sahara is a territory located between Morocco, Algeria, and Mauritania in the northwest of the African continent. Following the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, Spain conducted numerous expeditions to secure possession of Western Sahara (Fuente Cobo & Mariño Menéndez, 2006, p. 14). This was followed by years of Spanish occupation, exploitation of natural resources, and the transition of the territory from a protectorate to a Spanish province in 1958.

After decades of Spanish colonialism, the Polisario Front (Frente de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro) was founded in 1973 with the aim of liberating Western Sahara from Spanish colonialism and achieving independence. However, the expansionist ambitions of neighboring countries, Morocco and Mauritania, led to the Tripartite Agreements of Madrid in 1975, in which Spain abandoned the territory and divided it between these countries without considering the Sahrawis’ right to self-determination. This triggered a war between the Polisario Front, Mauritania, and Morocco.

Eventually, Mauritania signed a peace agreement with the Polisario Front, but King Hassan II of Morocco carried out the so-called “Green March” in 1976, during which hundreds of thousands of Moroccan civilians invaded Western Sahara. This invasion included attempts of genocide by the Moroccan military and air force against Sahrawi civilians fleeing into the desert, causing significant casualties amongst women, children, and the elderly—the core population fleeing as most Sahrawi men enlisted in the military. Those who successfully fled found refuge in Algeria, in the Tindouf region, where Sahrawi refugee camps are still located today (Ruiz Miguel, 2022, pp. 44, 45).

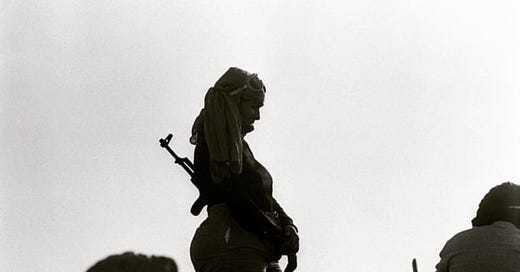

Consequently, after the Green March and air strikes, Sahrawi women who left the territory and survived in exile had to assume diverse responsibilities and roles within Sahrawi society. While men took up arms and went to war, women took primary leadership roles in the Sahrawi camps. Many also joined the military.

When Sahrawis fleeing the conflict settled in the inhospitable conditions of the Tindouf desert in Algeria (lhammada, as we call it), women were responsible for constructing the refugee camps with minimal resources.

"(...) Women took charge of helping, organizing the camps, channeling the scarce aid that arrived, and distributing it among citizens coming from various places." (Beiruk, 2022).

Meanwhile, in occupied areas, women and weaker elderly individuals predominantly remained, suffering persecution and abuse by the authorities.

Applying the concept of double colonization to the Sahrawi woman

Double colonization refers to the double oppression suffered by women from colonized nations due to their race and sex (Ahmed, 2019, p. 5). That is, first as subjects of colonization and second as women under patriarchy (Mishra, 2013, p.132). This dual marginalization stems from them being seen by the imperial power not only as subjects to be conquered but also as female individuals to be used and discriminated against, "whose voices and actions have been silenced, drastically reinterpreted, lost, or consciously erased." (Nejat, 2014, p.1). In the most general definition of double colonization, it is explained that women from colonized contexts survive under the imperialist oppression of colonial power and simultaneously endure patriarchal oppression from their cultural context.

In the case of the Sahrawi woman, it can be stated that the double oppression she suffers resides in her identity as a Sahrawi person under Moroccan occupation, her condition as a woman under Islamic societal expectations and ideals, and lastly, her vulnerability to the Moroccan forces of occupation due to gender/sex. According to a study compiled in The Oasis of Memory, by Martín Beristain and González Hidalgo (2012):

"Violence against women in the framework of Sahrawi culture and more broadly in Maghreb countries is experienced as an aggression against collective identity and dignity. While men were treated with particular cruelty during periods of enforced disappearance or arbitrary detentions and torture, women experienced these same violations from the abyss of aggression against their roles and the rupture of respect for their identity simply for being Sahrawi women. (...) Many of them had no political activism and were subjected to brutal repression due to family relations or their status as women."

It is important, first of all, to make a distinction or division between Sahrawi women. On one side, there are the Sahrawi women living in the occupied lands of Western Sahara. On the other, the women surviving in exile in the refugee camps mentioned before. Both have experienced the consequences of the war in one way or another, but their experiences have differed completely due to their diverging contexts.

According to Suelma Beiruk, Sahrawi women in the occupied zones have always been a primary target among the Sahrawi civilian population to suffer persecution and abuse of various kinds.

It is particularly difficult to obtain records of sexual violence cases during conflicts, and one of the main reasons for this is the difficulties female victims face when giving testimonies, in fear of the social repercussions that could result (Mendia Azkue & Guzmán Orellana, 2016, p. 59).

"In Western Sahara, when trying to ascertain the extent of the sexual violence perpetrated during the conflict and occupation, we encounter these same difficulties. First, there are no systematic mechanisms to gather these facts, and second, most who survive the violence choose to remain silent." (Mendia Azkue & Guzmán Orellana, 2016).

In the book In Occupied Land. Memory and Resistance of Women in Western Sahara by Idoia Mendia and Gloria Guzmán, testimonies of Sahrawi women are cited, expressing firsthand their fear of sharing stories of sexual violence, preoccupied of being blamed because of cultural and religious reasons. It was also implied that it is not advisable nor worth it to endure such consequences, due to their limited expectations of obtaining justice because of the occupation and the power dynamics in the territory, which guarantee the impunity of the perpetrators.

On the other hand, there are threats from Moroccan security forces if the victims report their sexual abuse, which results in great repression for the survivors. For example, the case of Hayat Erguibi, who was kidnapped numerous times by Moroccan authorities and subjected to rape, torture, and abuse during interrogations, declaring about one of these kidnappings that took place in 2009 when she was only 16 years old:

“They threatened me not to say anything, telling me that if I said anything about it, they would rape me again, but worse next time (...). Just because we are Sahrawis, this happens to me and other girls (...). They swore that if I gave any testimony, they would rape me worse that time, and then bury me somewhere that no one would know, and ‘no one would remember you.’”

This is evidence of double oppression, as on one hand, they are raped by the occupying forces, and on the other hand, they cannot report it, not only because of the threats from their rapists but also because they cannot even do so within their social circles due to the fear of rejection. It could be considered “triple” oppression, as they are targeted by the occupying authorities for being Sahrawis, suffer sexual violence from those same authorities for being women, and as a result, are forced to adhere to cultural patriarchy by being unable to publicly report it.

In contrast, in the Sahrawi refugee camps, there is considered to be a “great balance” in terms of relationships between men and women (Higgs & Ryan, 2015, p.33). In a report by Johanna Higgs and Christine Ryan, it is stated that in the Sahrawi community of the refugee camps, the prevailing idea is that there is “no violence against women” in their society. It is claimed that throughout the study conducted in the camps, women did not talk about violence or rape when asked about the difficulties they faced. It should also be considered that throughout the study, the cultural and religious implications of testifying about the abuses are overlooked, so it is likely that the interviewed women omitted information.

On page 37 of this report, a case is mentioned where a man physically abused his wife in the refugee camps, and she divorced him and took another man as her husband. The man remained alone, as no woman wanted to marry him. In general, it is believed that in Sahrawi society (in the refugee camps, where it doesn’t attempt to coexist with and isn’t influenced by the occupier’s society), men who commit violence against women are condemned and rejected when the act becomes publicly known. Moreover, in Sahrawi culture, unlike in similar cultural contexts, divorce is not demonized; it is viewed positively and even celebrated (Higgs & Ryan, 2015, p.36).

However, it is important not to overlook or dismiss certain social perspectives that harm Sahrawi women and their emancipation in the refugee camps. While Sahrawi women have rights that many women in similar contexts do not, they acknowledge that there are elements in their society that work against them, such as social rejection of unmarried pregnant women, among others (Martín, 2014, p.23). This contradicts the cited study. Therefore, I believe that the study by Higgs and Ryan does not delve deeply enough and is somewhat simplistic, as it makes generalizations that are not entirely accurate.

Furthermore, these statements highlight a clear contrast between the occupied territories and the refugee camps. In the camps, the experience of the woman is one of respect, leading and fighting for the right to self-determination while asserting her rights, while in the occupied territories, women are discriminated against and silenced by the occupying forces and violently repressed.

According to Suelma Beiruk, although Sahrawi women in the refugee camps have fought for their rights within their own society, this struggle has been respected and not repressed, unlike in the occupied territories. Beiruk states that in the Constitution of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, women have the right to participate, hold positions, and stand for candidacy. Furthermore, there are high percentages of female participation in key institutions of responsibility (Parliament 34%; Diplomacy 22%; African Parliament 45%; Government 21%) (Interview with Suelma Beiruk, 29/09/2022).

Returning to issues such as divorce, another notable comparison is the laws regarding women. There is a significant divide between Sahrawi women and Moroccan women living in the occupied territories due to the cultural gap. For example, the 2004 Moudawana law in Morocco marked a step toward greater equality in divorce, but discrimination against women in the Moroccan legal system still made the process difficult (March, 2019, p.1). However, the normalization and celebration of divorce in Sahrawi culture were in contrast to the social degradation of divorced women in Moroccan society.

This disparity would pose a difficulty for Sahrawi women seeking divorce that they would not experience if it were not for the occupying government and its laws. It is also a case of double oppression, as the Moroccan legal system would obstruct certain legal matters for Sahrawi women in a similar way to Moroccan women, and it could even be assumed that these issues would be more difficult for Sahrawi women due to political reasons, something that would not occur in the refugee camps, where the laws of the SADR apply.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Sahrawi women have suffered various consequences due to the Moroccan occupation, which are paralleled in the case of women living in the occupied territories and women in the refugee camps. They are not only targeted by the occupying forces for being Sahrawis, but they are also subjected to abuse, kidnapping, and arbitrary detentions explicitly for being women.

In the refugee camps, where Sahrawi culture has been more preserved and the laws of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic are adopted, women have had to assume primary roles and also became part of the liberation movement in a more direct manner. However, despite the positive aspects related to their rights, many social, cultural, and religious ideals limit them, particularly concerning their image and ostracism. This has resulted in an internal oppression related to pressures that influenced their decisions in social and family matters. The external oppression, on the other hand, corresponded to exile itself and the refugee status, a consequence of the occupation and the abuses by Moroccan security forces.

On the other hand, women in the occupied territories are deprived of even more rights. Both Sahrawi men and women suffered torture and kidnapping, but sexual abuse was more prevalent against women (which have also gotten pregnant from rape in some occassions). In this case, external oppression corresponds to the shared problems faced by Sahrawi men and women in the occupied territories. Meanwhile, the second layer of oppression is attributed to their condition as women, whether from the authorities or from the religious and cultural customs and perspectives of Sahrawi society, as seen in the case of women in the refugee camps.

In sum, both women, in the camps and in the occupied territories, have lived through double oppression, which in some cases has even been “triple”. Each woman has had her individual experiences conditioned by her environment, whether under the harshness of the occupation and its oppression or the survival challenges in the desert, constituted by cultural expectations and the assumption of roles.

It is therefore relevant to state that, in the event of independence and the return of people from the refugee camps to Western Sahara, there will be an imbalance between women due to the rights gap. This will be a consequence of the lack of education for women in the occupied territories and the repression of their freedom of expression.

However, it is crucial not to overlook the active processes of Sahrawi women working to improve their reality, and all their efforts to fight against all forms of oppression they are victims of. Furthermore, their role in the fight for liberation has been nothing short of admirable, which is why they’re living images of resistance and resilience.