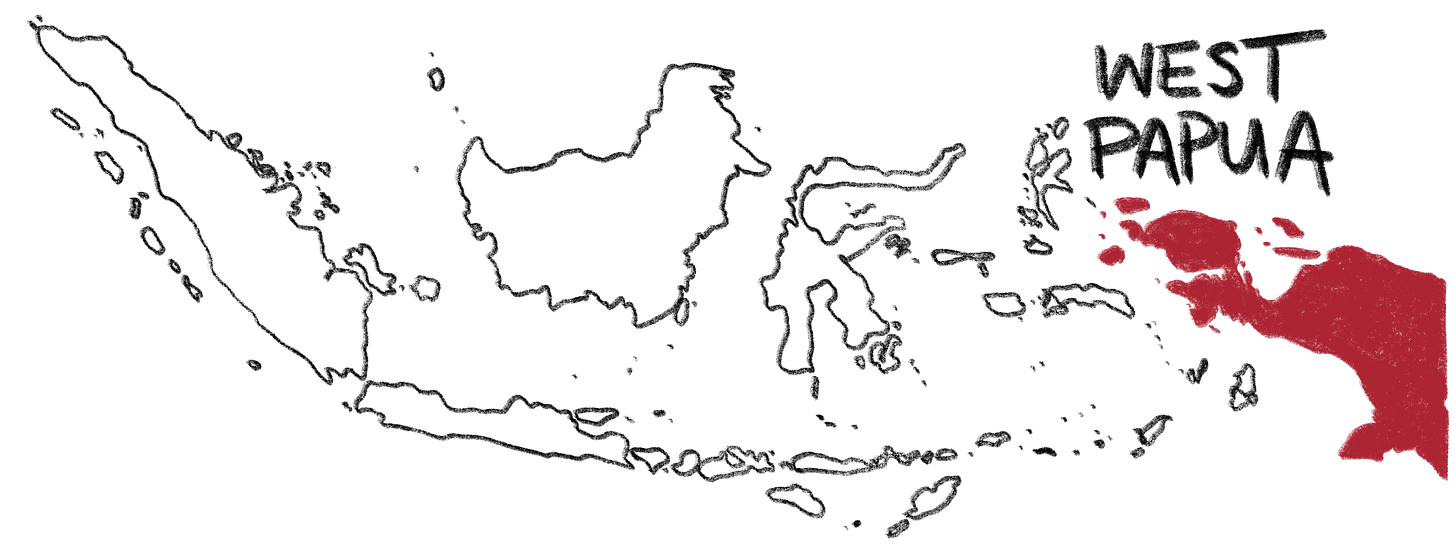

State Control, Sexual Politics: Reproductive Resistance against Bio/Necropolitics in Occupied West Papua

"Reproductive technology, in the hands of midwives and their patients, could be an example of this more autonomous exercise of reproductive resistance."

By Safira & Rafa

In 1965, the overthrow of Sukarno as Indonesia’s first President by US-backed General Suharto’s military coup marked the beginning of an authoritarian era. Sukarno’s anti-imperialist policies accompanied by strong presence of communist groups such as the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), were viewed by the United States as a direct threat to them. The period after the coup became infamously known as The Jakarta Method, referring to the systematic violence of mass murders that took place under Suharto’s regime, which occurred with significant material support including weapons and financial aid to the Indonesian military by the US. This violent anticommunist purge targeted suspected communists or those who were deemed as political enemies, which oftentimes were unarmed innocent civilians.

In the 1970s, through agencies like USAID¹ (United States Agency for International Development) and the Ford Foundation², the US became a driving force behind Indonesia’s family planning program called Program Keluarga Berencana (KB) (hereinafter ‘Program KB’). What initially appeared to be “humanitarian initiatives” aimed at controlling population growth has revealed itself to be a far more sinister project.

Framed as a means of stabilizing the country’s growing population with the famous slogan “Two Kids are Enough!”, these initiatives were deeply intertwined with the US’s imperialist goals. They represented a form of biopolitics—a method of controlling populations through state-sanctioned practices, policies, and interventions. Under the guise of population control, Suharto’s developmentalist regime actively reduced women to mere baby-making machines, removing their reproductive rights and blatantly dehumanizing women. Reproductive decisions were no longer personal, but imposed by the state.

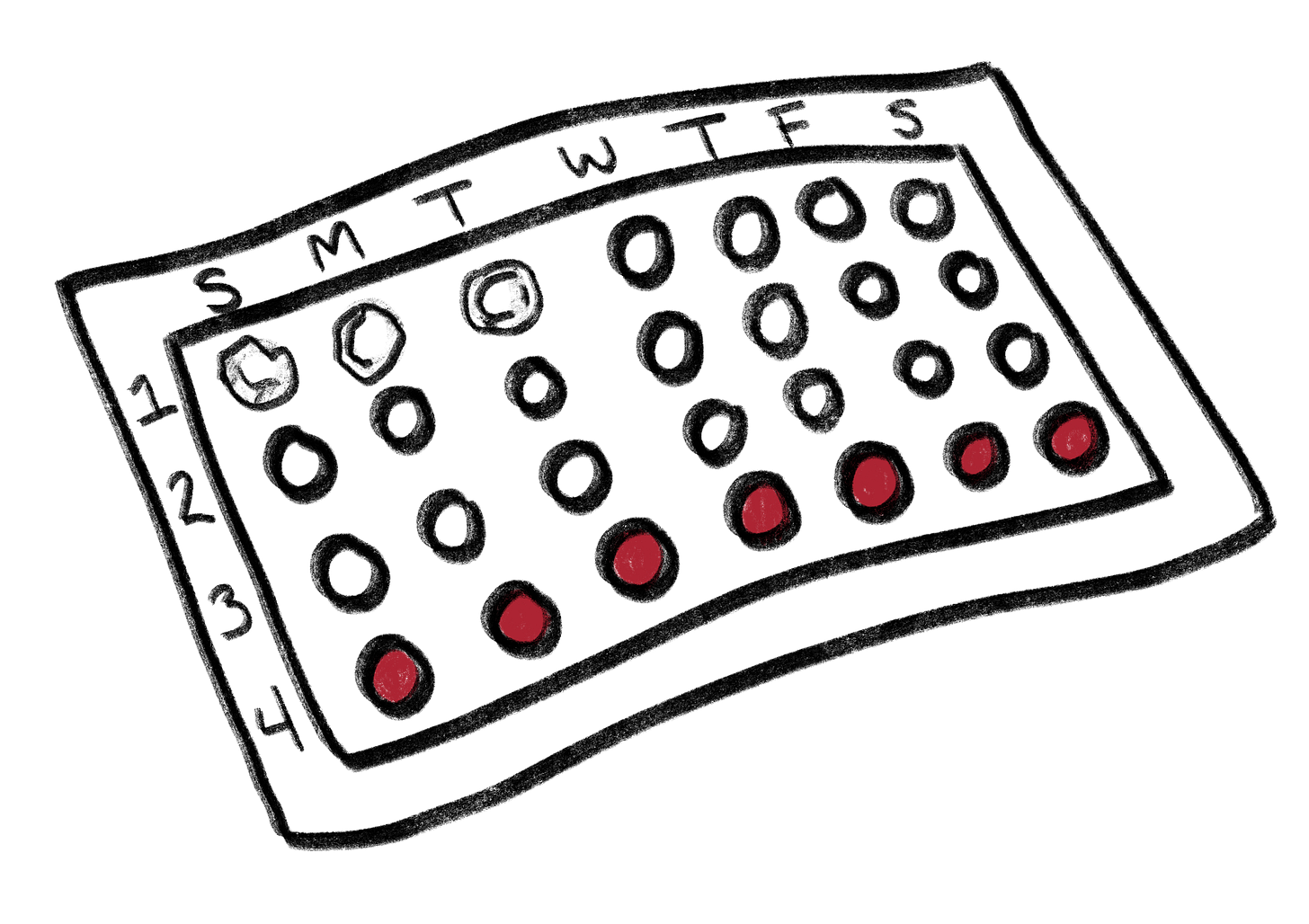

The program enrolled married women as automatic “acceptors” of state-mandated contraception, forcing them into a system of surveillance and control. This program was not just about controlling birth rates, it was about controlling life itself—an exercise in necropolitics³, where the state dictated who could live and thrive, and who would be reduced in number, strength, and resistance.

In her article ‘Kita habis…we will be gone’: The politics of population, family planning, and racialization in West Papua, Rasidjan (2023) wrote about how Indigenous Papuans expressed concerns about their extinction (kepunahan) and being “eradicated” (kita habis) due to a steadily decreasing Indigenous population. Program KB alone resulted in a declining birth rate by over 50%, from a rate of 5.9 to 2.6 children per woman from 1970 to 2000. The 2000 census showed a significant gap in fertility rates between nonPapuans and Papuans in West Papua, with the ratio reaching 10:1.

A Dani priest (Indigenous ethnic group in West Papua) described birth control as government genocide (Butt, 2001). In West Papua, where the Indigenous population was already being politically marginalized, the initiative of Program KB was a direct tool of genocide— pushing the Papuan population into demographic decline and facilitating their eventual erasure.

The biopolitics of Program KB resulted in racialized subjectivities, because it produced a dichotomy between ‘Indonesians’ and Black Indigenous Papuans, thus concretizing racism. This form of racism was not enforced through anti-miscegenation laws, such as bans on interracial marriages, but rather through the increasing presence of ‘mixed marriages,’ which is seen as a form of racial and cultural assimilation, wherein ‘being less Black’ is equated with ‘being pretty’ and a symbol of progress. The image of the idealized Muslim Malay two-child family, which was framed as the model of modernity and national progress, marginalized and othered Indigenous Papuans in contrast to this vision.

Quoting from Rasidjan’s article (2023), she cites a Malay-Western Indonesian government health clinic midwife who reflected on the transformation of the region. The midwife commented,

Before, the road from Sentani to Abepura was just all trees. It is so amazing now, if I may say so. When I arrived in 1985 as a newcomer (pendatang), it looked far and away different from now. It appeared that the people from this area and newcomers were quite distant from each other. And now, it’s so different! Papuans are pretty (cantikcantik) now. They are in mixed marriages, so they’re very pretty.

That statement revealed how Indigenous Papuans are positioned as subjects to be destroyed by the dominant power structures of the Indonesian state. The reduction of forested land and the increasing presence of ‘mixed marriages,’ reinforces a racist vision of development that associates environmental degradation and mixed marriages with a desired cultural and racial transformation.

While the Indonesian government has long promoted Program KB to control population growth, local leaders, including midwives, have taken a different approach. Some local leaders, seeing population growth as vital for the survival and empowerment of the Papuan people in the face of Indonesian colonization, have actively incentivized Papuan women to give birth. They offer prizes to encourage childbearing, attempting to counter the impact of state policies that would reduce their population, a few examples in many cases:

In 2014, Papuan governor Lukas Enembe awarded cash prizes to heads of Indigenous Papuan families (who were mostly men except for two women) who had 10 or more children;

Bapak Dortius’s administration in 2011, following Lukas Enembe, began a pronatalist program where women were offered a cash “incentive” each time they showed up pregnant to the local government-run health clinic. He introduced the program by noting that it would “increase the growth of Papua’s orang asli (Indigenous population)”.

The quote from Ibu Teresa, a midwife, highlights this tension in Rasidjan’s piece (2023). She acknowledges that encouraging women to have more children could be “good for Papuans to perhaps increase [in number].” However, she raises concerns about the potential risks involved, particularly when women, motivated by the financial incentives tied to childbirth, might be encouraged to have children at older ages.

Midwives—caught in a tug-of-war between the Indonesian government and local Papuan leaders, face an ethical dilemma as providers and deniers of birth control. They are trained and employed by the Indonesian government, which expects them to promote Program KB. However, they also serve Papuan communities where local leaders discourage or outright ban contraceptive use. Despite the pronatalist policies, many midwives continue to provide contraceptives to women who request them. They recognise the individual needs and desires of their patients, even when those desires conflict with government mandates. Midwives also recognise that women have diverse needs and circumstances. They aim to provide care that addresses those individual needs, rather than simply adhering to programmatic targets. They carefully calculate what to reveal to whom, building trust with their patients to understand their needs and provide appropriate care.

These dynamics reveal that despite women’s bodies being controlled externally where reproductive choices are policed and manipulated by political and economic agendas, women (in this context patients and their midwives) persist in personal resistance and navigating these struggles.

Reproductive technologies like contraception are often considered “feminist technologies” because they give women the “choice” to reproduce, an illusion of agency by liberal feminism. However, we believe reproductive technologies that are considered feminine— such as birth control pills, tampons, pregnancy tests, etc.—cannot be automatically classified as feminist technologies. For example, contraception historically has been used as a tool for men to control women’s bodies, especially Black women. Program KB and other biopolitical programs like it are often invisible to the rest of the world, and it exposes contradictions of reproductive technology when used within colonial, capitalist, and patriarchal systems. The patriarchal contradiction here is that contraceptives as a reproductive technology, which could support women’s reproductive rights and autonomy, are instead used to control and limit women’s bodies and completely eliminate women’s autonomy. Indigenous Papuan and Indonesian women’s bodies are reduced to tools for reproduction, serving the needs of the community and the state, rather than recognizing women’s self determination.

While these technologies can be helpful, they do not necessarily lead to substantial improvements in women’s lives within patriarchal societies. Instead, they only allow women to adapt to the existing social structures, rather than fundamentally shifting the power imbalance between women and men, and eventually destroying the shackles of women’s oppression.

While the Indonesian state implemented Program KB through institutions like BKKBN, Papuan local leaders imposed their own restrictions on women’s reproductive autonomy through the outright ban of contraceptive use. Despite the apparent contrast in their approaches, both systems are rooted in the idea that women’s bodies exist as objects of control, whether through population control in the form of contraception or through the rejection of contraceptive technologies to resist population control. At the heart of Program KB lies the exploitation of women’s reproductive capacities, where they’re culturally pressured to make their bodies an arena of political contestation dictated by male leaders, the state, and imperialist forces.

On the basis of the reasons and stories we have unfolded above, we firmly reject the use of technology to control women’s bodies and reproductive organs by male leaders, as well as the practice of necropolitics and biopolitics for the imperialist state or for any other reasons imposed upon us.

We also would like to highlight a fundamental dichotomy between state-imposed control and autonomous reproductive choice: while the states and local leaders enforce reproductive control and coercion through its policies, midwives and their patients made a space where reproductive choice could be autonomous. Reproductive technology, in the hands of midwives and their patients, could be an example of this more autonomous exercise of reproductive resistance. In this context, women are able (albeit in limited ways) to decide what to do with their bodies, whether to access reproductive technologies like contraception, or to reject coercive practices such as Program KB and instead choose to bear children.

The involvement of midwives and their patients in this process highlights the potential for feminist institutional change. In contrast to the patriarchal control embedded in Program KB, this grassroots practice shows the potential for a feminist and localized form of reproductive care that values self-determination. If institutionalized nationally, this approach could benefit all women in Indonesia.

We believe that women, as an oppressed and marginalized class, must seize technology from the hands of our oppressors and turn it into a tool of collective liberation by tearing down this oppressive system and rebuilding it with a more just and equal system, based on Feminist Ecosocialist Technology (FET)⁴ values. We reimagine technology as a force for collective good, capable of nurturing both human and ecological life. This is the feminist technology that we demand—one that nurtures life and liberates both women and nature.