Surviving in Silence: Aboriginal Women’s Resistance to Rape and Sex-Based Violence

A powerful exploration of the intersection of colonialism, racism, and patriarchy in early Australia.

By an Anonymous Author

'There are no white women at all. On these the Aboriginal women are usually at the mercy of anybody, from the proprietor or Manager, to the stockmen, cook, rouseabout and jacked’. —With the White People, Henry Reynolds, 1990

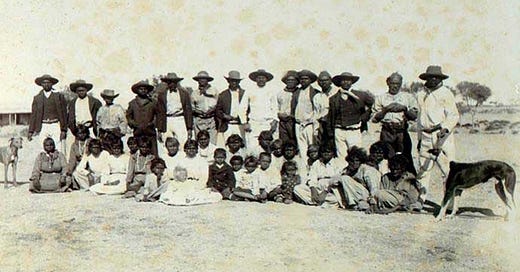

It is no secret that mass rape and sexual abuse have always played a central role in settler colonialism. There has been not one exception to this rule. In early Australia (1788–1900), this sex-based violence was further exacerbated by the lack of female settlers, leaving Aboriginal women as the only female presence in the country and putting them at the mercy of entire working stations.

Settler men found themselves further emboldened by racist stereotypes, conveniently pushing the idea of Aboriginal women having no pre-existing ideas of chastity, and therefore in the eyes of Christian men seen as deserving of their sexual degradation. In one striking example of the complete disregard for Aboriginal women’s bodily autonomy, during the South Australia Royal Commission in 1899, a cattle farmer in Nullarbor Plains was quoted saying,

‘...Every hand on the place had a gin (slang for Aboriginal women), even down to the boys of 15 years of age’.

Similar comments have been observed in Royal Commissions Australia-wide. Mounted constable William Willshire took this dehumanisation to the next level, believing that God meant for Aboriginal women to be used by white men, ‘as he had placed them wherever pioneers go.’ He, like many settlers in early Australia, regularly found himself bragging about his ‘Gin busts’ (the practice of gang raping Aboriginal women). Police/law enforcement were not a safe place to turn to, with Aboriginal women reporting being gang raped in their cells.

Predictably, in such a volatile climate Aboriginal women were forced to find alternative measures to protect themselves and their communities.

In this piece I will be speaking specifically about the sex-based violence pivotal to the formation of settler colonies in early Australia while showing my admiration of my people’s long-standing fight and our history of civil disobedience in the face of a nation built off our sexual trauma.

The role of opportunity in sex-based violence cannot be understated; when the opportunity to commit such acts intersects with the pre–existing dynamic of settler impunity against the native population, it creates the uniquely horrible conditions colonialism enforces on women.

Australia was at first a British Penal Colony. This nation’s very purpose was to expel undesirables, individuals who, in the eyes of the British government, were not to be trusted with the general populace. In the 1828 New South Wales census, only 24.5% were women (this census only counted the white population of course, with Aboriginals only gaining status of British subjects in 1949). A gender ratio skewed towards men always leads to catastrophe for the few women unlucky enough to be in their proximity. This behaviour was emboldened towards Aboriginal women, who not only were seen as ‘promiscuous by nature’, but also simply not classed as citizens.

To be a woman classified as ‘free game’ is a death sentence. The Abo whore-to-be was seen in direct contrast to the pure British Madonnas.

I started off this piece with a direct quote included in Sexual Assault: Issues for Aboriginal Women by Carol Thomas, the Aboriginal Women’s Policy Coordinator, where it is bluntly stated by a station worker, ‘Aboriginal women are at the mercy of everybody’. Early Australia was the perfect storm for the mass gangrapes, paedophilia and widespread sexual abuse of Aboriginal women. A penal colony, overwhelmingly male, with an open embrace of any practise that asserted dominance over the natives.

This power dynamic was further enforced with the creation of indentured servitude; white men’s existing impunity had perceived racial superiority on their side, and with the introduction of indentured servants, class was now another factor of Aboriginal women’s oppression. Early 20th century Australia was largely defined by the creation of ‘Aboriginal Protection boards’, in which Aboriginal girls were systematically taken from their families and groomed to be maids for white families or (depending on their skin colour) adopted by white families to forcibly assimilate. It cannot be stressed enough how severe the mass sexual exploitation was in these environments.

In 1915, Archbishop Donaldson visited Barambah and noted that ‘over 90%’ of the girls sent out to service came back pregnant to a white man (Bringing them Home p. 66, Australian Human Rights Commission, 1997).

Aboriginal domestics, despite such shocking conditions, were known to regularly participate in station strikes alongside the men, most notably the Pilbara Strike of 1946–1949. This was an iconic moment in Aboriginal history with the strike resulting in higher wages and better working conditions. The ripple effect of said strike was felt country wide, with working stations everywhere following suit. Domestic workers ran the inner workings of stations, their involvement drastically impacting the effectiveness of a strike.

‘Black velvet’ was a commonly used term for Aboriginal women in early Australia, a sexual allegory seeped in racial fetishisation. In a pathetic effort to both alleviate guilt and shift responsibility, the colonists stereotyped Aboriginal women as having insatiable sexual drives and animalistic tendencies. This is of course a laughable assertion, simply further proving the predictability of settler colonialism.

The Native American woman, the Black woman, and the Indian woman were all collectively referred to as hypersexual animals by their colonist counterparts. Racial fetishization and the patriarchal eroticization of female vulnerability contribute to a damaging narrative in settler colonies: the idea that the ‘native woman’ inherently desires rape, driven by an insatiable sex drive. When she expresses that this isn’t what she wants, that in fact she is no less affected by gangrape as white women, she is laughed at, because everybody knows us savages do not have the intellectual capacity to fathom being violated; we were born to simply spread our legs and take it. As the good Christian man Mounted Constable William Willshire said, God had meant for Aboriginal women to be used by white men as ‘he had placed them wherever pioneers go’.

The abuse that Aboriginal women faced often affected them for much longer than the initial attack, which was exacerbated due to overwhelming support for the government’s funding of this very abuse.

In the above paragraphs I spoke on sex-based violence, primarily regarding rape, but what about the results of this intercourse? It is in no way controversial to say (at least in radical feminist spaces) that reproduction is a continuation of the trauma of rape. The resulting offspring of this widespread sex-based violence were then further utilised to control and traumatise victims. The lighter ‘half caste’ children of Aboriginal mothers found themselves preyed on by white families looking for domestic servants, or more bluntly, domestic slaves, as there were no protections in place to ensure wages. It is common knowledge in our community that when the ‘Native police’, or as it was condescendingly named in later Australia, ‘The Aborigines Protection Board’, would knock on your door, the fair skinned children would have designated hiding spots so as to not be taken.

‘We were told to be on the alert and, if white people came, to run into the bush, or stand behind the trees as stiff as a poker, or else run behind logs or run into culverts and hide.’—Witness number 681, National Inquiry into Stolen Children, 1995–1997.

The psychological torment inflicted upon Aboriginal mothers is tragically under-researched. These women endured repeated rape by white men, were forced to bear the children conceived through those rapes, and then, once deemed ‘old enough’ by White Australia, saw their children that they loved despite the circumstances of their birth be torn from their arms.

As with all groups who were dehumanised to such a severe extent, we must come up with our own creative ways to practice self-determination. For example, Aboriginal women would use a mixture of charcoal and animal fat to artificially darken their half caste children to fly under the radar of those in want of a houseslave-in-training, engaging in workers strikes as well as keeping cultural practises, family structures and language alive. Despite the distinctively cruel nature of our oppression as females of the native class, and with few allies outside of ourselves, Aboriginal women have persevered. This country is still of course still the cesspool of the Pacific. The general population has never and in my (somewhat pessimistic) opinion will never place value in our lives, but alas we persist. We continue to refuse to leave our land, culture and communities.